Scrolling through social media, you might see pictures of cute cats. An interface between our personal and social lives, pets’ photos help us express ourselves while keeping a distance. An old trick. Just as we post pictures with cats, Song Dynasty literati (well-educated scholars and/or officials) exchanged poems about the reclusive flowering plum.

By Ilina Tatiana

What are they like,

Half blossoming, half fading, midst briars and thorns?

A lovely woman, desolate, among grasses and trees?

A high-minded gentleman, thwarted, among brambles and weeds?

– Wang Anshi (1021-1086)

To get some clues as to what poet and politician Wang Anshi (1021-1086) is wondering about, we need to go back to the Southern Dynasties period, when poets first became attracted to plum blossoms. Then they are already not just a flower, as we see from a rhapsody by emperor-poet Xiao Gang (503-551) in which they almost turn into a palace lady, fearing for their falling petals just as the lady does for her passing beauty:

The spring wind blows plum petals – I fear they all will fall.

For this I, humble woman, knit my brows.

If flowers and beauties are alike,

We ever worry for fear of missing our time.

– Xiao Gang (503-551)

In contrast, scholar-poet Tao Qian (365-427) calmly admires the blossoms flanking the gate of his solitary abode.

Plums and willows were planted to flank my gate,

One branch now bears fine blossoms.

– Tao Qian (365-427)

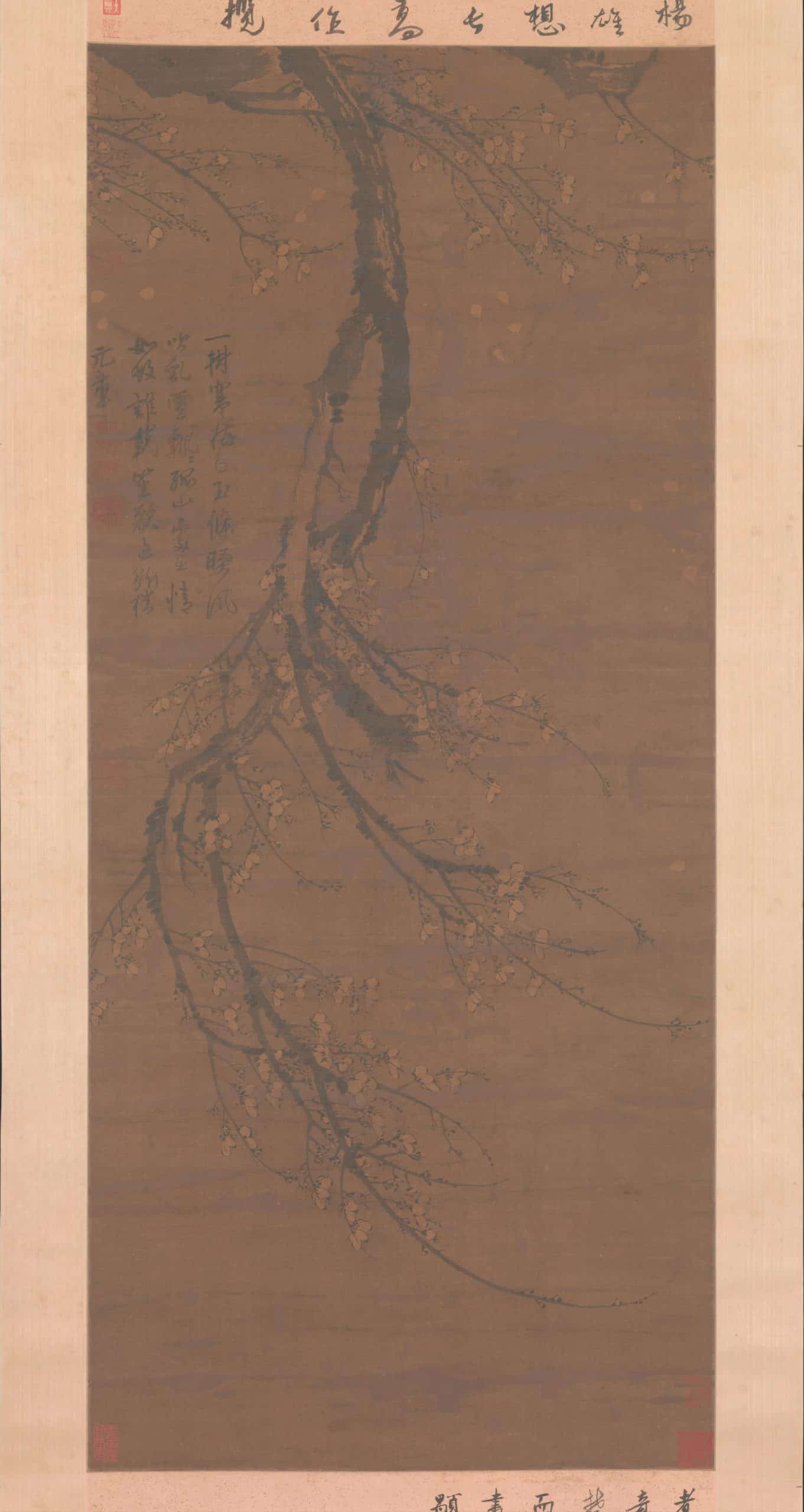

Reclusive literati and plum blossoms become almost inseparable in the figure of poet Lin Bu (967-1028). A lifelong bachelor, he lived in seclusion on Gushan Island in Hangzhou where he planted plum trees, raised cranes and wrote verses, ‘even and bland, profound and beautiful.’ Although he occasionally destroyed his poems and ‘hid himself away among groves and gullies,’ fame found him thanks to the efforts of his admirers – poets, scholars and emperors.

The triumph of Lin Bu’s calm poetry was mirrored by a revolution of dark ink wash paintings by Buddhist monk Zhongren (1051-1123). His ink paintings, depicting white blossoms with black dots, transcended the illusory appearance of flowers to manifest their essence. No works by Zhongren survived but suggestive of them are the works of another monk-painter Muqi (mid 13 c.)).

Painted for pleasure, Zhongren’s works became known through the poems and writings of his friends, influential literati, who met the monk during their exiles in the South. With one of his guests, scholar Huang Tingjian (1045-1105), the monk shared verses about plum blossoms by poets Su Shi (1037-1101) and Qin Guan (1049-1100); inspired by them Zhongren made a painting and Huang Tingjian composed a poem – both about the flowering plum.

Like most of Su Shi’s poems about plum blossoms, he wrote the one shared at this encounter in exile. In these introspective works, the flowering plum conveys loneliness, be it wild plums blossoming on a mountain pass or blossoms with ‘bones of jade’ and ‘soul of ice’ embodying his concubine.

In the Plum Blossom Village at the foot of the Lo-fu Mountain,

The bones of the flowering plums are of jade and snow, and their souls are of ice.

In their multitude the blossoms seem moonlight hanging from the trees,

In their brightness they blend only with Orion on the horizon.

– Su Shi (1037-1101)

Later, during the Southern Song (1127–1279), the fusion of the plum and the blossom-like lady came to represent an abandoned woman in sorrow. Personified in the fictional character of a forgotten consort of emperor Xuanzong (685-762) in historical romance “Biography of the Flowering-Plum Consort,” the image was borrowed by poet Li Qingzhao (1084-1151) to tell her own story as a widow during the turmoil of the early 12th century, when the Song Dynasty was ousted from its northern territories and fled to the South.

Year after year when it snowed

I’d often stick plum blossoms in my hair and get drunk;

I’d crush the plum blossoms with ill will

And get my clothes all drenched with pure tears.

This year, out of the way at the edge of sea and sky,

The hair on both my temples blossoms white.

I see the evening wind is so strong,

It will be hard to find plum blossoms.

I just crush the stamens,

Just to wring out a little more fragrance,

Just to prolong the time.

– Li Qingzhao (1084-1151)

At that time, seeking to express their pursuit of solitary lifestyles, literati more than ever favored the flowering plum. Constructing a self-image of seclusion, the poets underscored the plum’s early flowering, to set it apart from other flowers and expanding its singularity to include its admirers, the poets themselves.

Plum blossoms and I rather sing the same tune…

In ice and frost as the year grows old our spirit only grows stronger;

Not to be compared to the flourishing flowers that so easily wither and scatter. – Wang Mian (1287-1359

Exploring plum’s poetic possibilities, literati expanded beyond art into life, at times going to extremes – they would chew plum buds to get some fresh verses, make a plum-flower chicken soup or a tent to sleep among plum trees. No matter how creative their flowering-plum worlds were, they had a foundation of thorough literary research and boundaries. To be allowed in, you had to learn the Dos and Don’ts of plum blossom appreciation. ‘In delicate shade’ or ‘in early morning sun’ would do well, but in no way should it be ‘stuck in a vase inside a common tavern.’ Only the best for this most refined and solitary of flowers.

Did you know that plum blossoms inspired such depths of emotion in the ancient Chinese? Let us know in the comments below. We would love to hear your thoughts and insights on traditional Chinese culture!

| Author Bio: Ms. Ilina Tatiana is an art lover and culture hunter. |  |

Sources

男人不如狗?揭秘中国城市的“宠物奴隶”, https://renkou8gua.blog.caixin.com/archives/253135

Maggie Bickford, Ink plum: the making of a Chinese scholar-painting genre. (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 63

Hans H. Frankel, “The plum tree in Chinese poetry, “ Asiatische 6 (1952), 101

Ibid., 94

Bickford, 23

Ibid., 115-130

Richard M. Barnhart, Three thousand years of Chinese painting. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 125

李一冰 Li Yibing,苏东坡新传/ Su Dongpo xinzhuan. 成都:四川人民出版社(Chengdu: Sichuan renmin chubanshe,2020), 297

Bickford, 25

Ibid., 55-60

Ibid., 27

Ibid., 50

Hans H. Frankel, 111

Ibid., 113

Contact Us

Stay up-to-date with the latest offers, information and events from Cultural Keys. Follow our Official WeChat Account by scanning the QR code (click for larger image), or follow us on Facebook, Instagram or LinkedIn to be the first to know!

For more information about anything on this page, or for more information about Cultural Keys, please contact us or use the form below to let us know your specific requirements.

Recent Posts

Mouseover to see left and right arrows

Upcoming Events

Mouse-over to see left and right arrows

About Cultural Keys Chinese Culture Company

Cultural Keys helps you access, understand and enjoy life in China through traditional Chinese culture. Click here to read more about Cultural Keys and what we can do for you, your school, company or group to help you get more out of your time in China!